There was no pitch deck, no market sizing exercise, no grand vision of “disrupting” anything. It didn’t even start with the intention of building a product at all.

It started with frustration.

Not the dramatic kind. The quiet, recurring kind that shows up when you’re deep in the work and realize you’re solving the same problems over and over again—without a good system to support you.

This is a story about how Wonderflow came to be by solving my own problems first. Not because that’s a clever founder narrative, but because it’s the most honest explanation for why the product exists at all.

The Pain Came From Doing the Work

For years, I worked inside marketing teams and alongside clients where planning was always the weakest link.

Ideas lived in documents.

Campaign details lived in spreadsheets.

Assets lived across drives, tools, and inboxes.

Strategy lived mostly in people’s heads.

Everyone was busy. Everyone was moving fast. And yet, there was a persistent feeling that something fundamental was missing.

Campaigns were often launched before there was true clarity around:

- Who this was really for

- What problem we were solving

- How success would be measured

- How all the pieces fit together

Planning tended to happen after execution had already started. We’d run ads, build pages, write copy—and only later ask whether it all made sense together.

The more projects I worked on, the more obvious the pattern became:

marketing rarely fails because people don’t work hard enough. It fails because teams skip the thinking.

This wasn’t a hypothetical problem. It showed up everywhere. Across companies. Across team sizes. Across budgets.

And that repetition mattered.

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned from building products is that real problems don’t announce themselves loudly. They reveal themselves through frequency. When you feel the same friction often enough, it’s usually worth paying attention.

Early Assumptions I Got Wrong

Like most founders, I made a lot of assumptions early on—many of them reasonable, and many of them wrong.

I assumed:

- People wanted more execution tools

- AI should focus on generating outputs

- Faster always meant better

- Planning was something people “already had figured out”

These assumptions made sense in theory. They aligned with what the market seemed to reward: speed, automation, more features.

But they didn’t hold up once real users got involved.

In the earliest stages, the idea of Wonderflow lived entirely in my head. It was what you might call the gas phase of an idea—intuitive, blurry, and unproven.

As I started sketching things out, showing early concepts, and talking through workflows, the idea began to take shape. Some assumptions solidified. Others dissolved quickly.

What surprised me most was this:

people weren’t asking for more tools—they were asking for more clarity.

They didn’t want AI to replace their thinking. They wanted help structuring it.

Problem–Solution Fit Is a Process, Not a Moment

There’s a lot of talk in startup culture about finding Problem–Solution Fit, but it’s often described as a milestone—something you either have or don’t.

In reality, it’s much messier than that.

Problem–Solution Fit emerges gradually, as ideas move from:

- Gas: intuitive but unvalidated

- Liquid: shaped by feedback and experimentation

- Solid: tangible enough to test in real conditions

Wonderflow lived in that liquid state for a long time.

Instead of trying to appeal to a broad market, I focused on a small group of people who felt the pain deeply—marketers who were already improvising solutions just to stay organized.

These early users weren’t looking for perfection. They were comfortable with rough edges, missing features, and manual workarounds—as long as the core problem was being addressed.

That distinction matters.

Early adopters don’t buy polish. They buy relief.

What Early Users Surprised Me With

One of the most valuable parts of this process was discovering how wrong I was about what people actually valued.

I expected speed to be the main selling point.

I expected automation to be the headline feature.

I expected AI-generated outputs to be the “wow” moment.

Instead, users kept reacting to something else entirely.

They were excited about:

- Seeing their entire campaign laid out visually

- Being forced to slow down and think before launching

- Having a shared space where strategy lived

- Using AI as a thinking partner, not a shortcut

The most consistent feedback I heard wasn’t “this saves me time.”

It was “this makes me think more clearly.”

That changed everything.

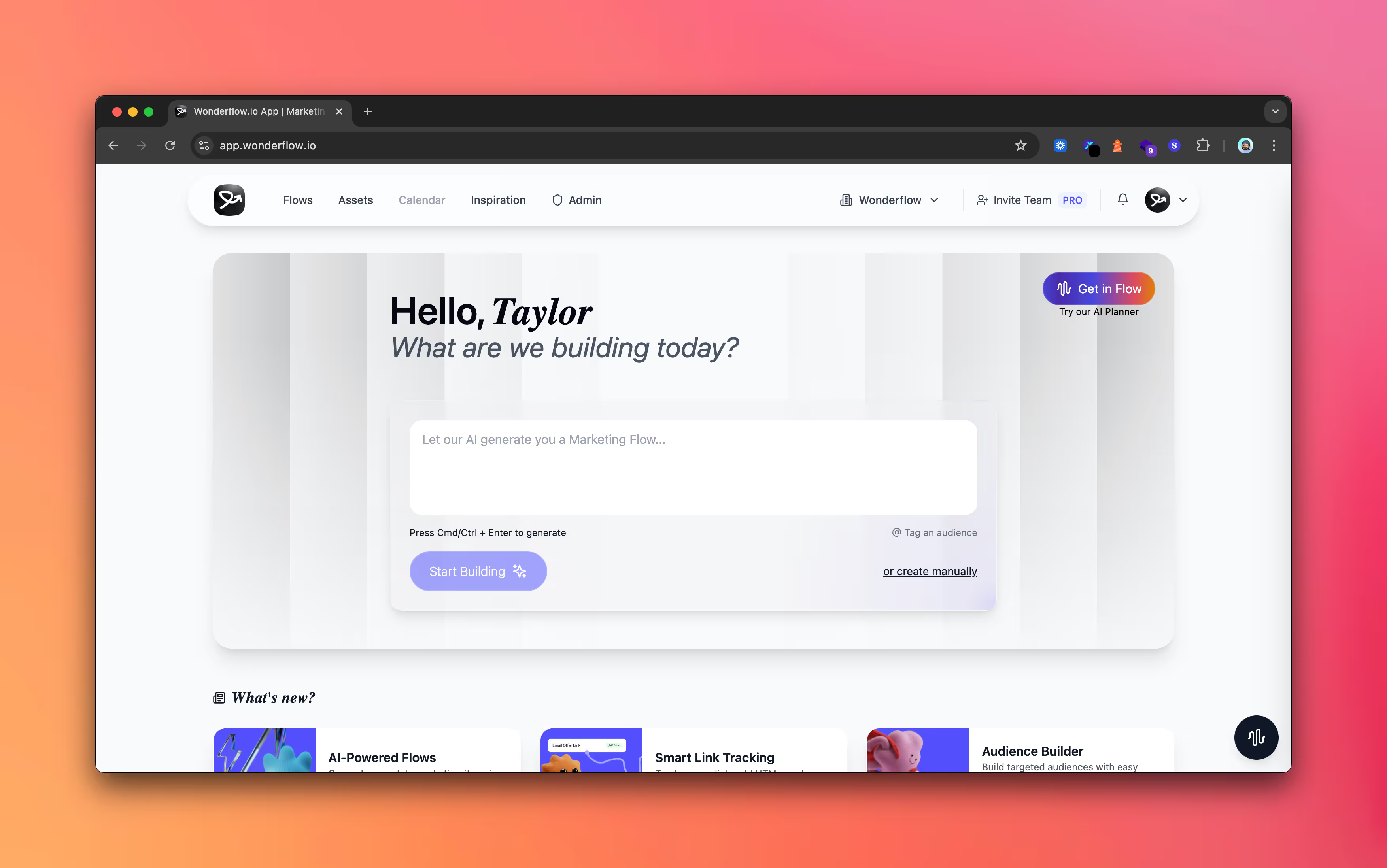

It reframed Wonderflow from an efficiency tool into a planning system. From something that does marketing into something that helps you think about marketing better.

Writing Things Down Changes How You Think

Around the same time, I found myself returning to a simple idea I’d relied on for years: writing things down is often the first real step toward solving a problem.

When problems stay in your head, they feel overwhelming. When you externalize them—through frameworks, diagrams, or simple lists—they become manageable.

This idea is at the heart of many effective problem-solving frameworks:

- Break the problem into smaller parts

- Reframe it from different angles

- Identify habits or forces contributing to it

- Work toward the root issue, not just symptoms

When applied to marketing, this approach consistently revealed something uncomfortable but useful:

the real problem was rarely the tactic—it was the lack of clarity upstream.

Wonderflow began to take shape as a place where this thinking could live. A canvas for planning. A system for making strategy visible.

Wonderflow as a Byproduct, Not the Goal

At some point, it became clear that Wonderflow wasn’t something I was deciding to build.

It was something that kept emerging naturally as I tried to solve the same planning problems again and again.

The product wasn’t driven by ego or ambition. It wasn’t about chasing trends or capitalizing on AI hype.

It was about answering a simple question honestly:

“What would actually make this work easier?”

Wonderflow became a byproduct of lived experience—of being in the mess, not observing it from the outside.

That origin matters, because it shaped everything that followed:

- A planning-first approach

- Brand-aware AI instead of generic output

- Collaboration built around context, not tasks

- A focus on clarity over velocity

Why Planning Comes Before Execution

Most marketing tools assume you already know what you’re doing.

They’re built to help you execute faster: launch ads, send emails, publish content. But they rarely ask whether those actions are connected—or whether they make sense together.

Wonderflow takes the opposite stance.

It assumes that thinking is the hard part.

That clarity is earned, not assumed.

That execution without alignment amplifies confusion.

By slowing teams down just enough to plan intentionally, Wonderflow helps prevent the downstream chaos that eats time, budget, and morale.

This isn’t about doing less marketing.

It’s about doing it with intention.

What I’d Do Again (and What I’d Avoid)

Looking back, there are a few things I’d repeat without hesitation:

- Starting with my own pain instead of a market thesis

- Talking to people who were already improvising solutions

- Staying focused on a small group of early users

- Letting the product evolve through use, not speculation

There are also things I’d actively avoid:

- Over-validating ideas in isolation

- Trying to build for “everyone”

- Mistaking interest for true problem depth

- Optimizing for scale before clarity

One of the most important lessons is also the simplest:

your time is more valuable than your ideas.

Protect it by working on problems that matter.

Build for the Problem, Not the Ego

Most products don’t fail because the idea was bad.

They fail because the problem was never deeply understood.

Solving your own problems first doesn’t guarantee success—but it dramatically increases your chances of building something real. Something grounded. Something useful.

Wonderflow exists because these planning problems kept showing up. And solving them once wasn’t enough.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned through this process, it’s this:

Build for the people who feel the pain.

Listen when they surprise you.

And let the product be a reflection of the problem—not your ego.

That’s how Wonderflow came to be.

.avif)